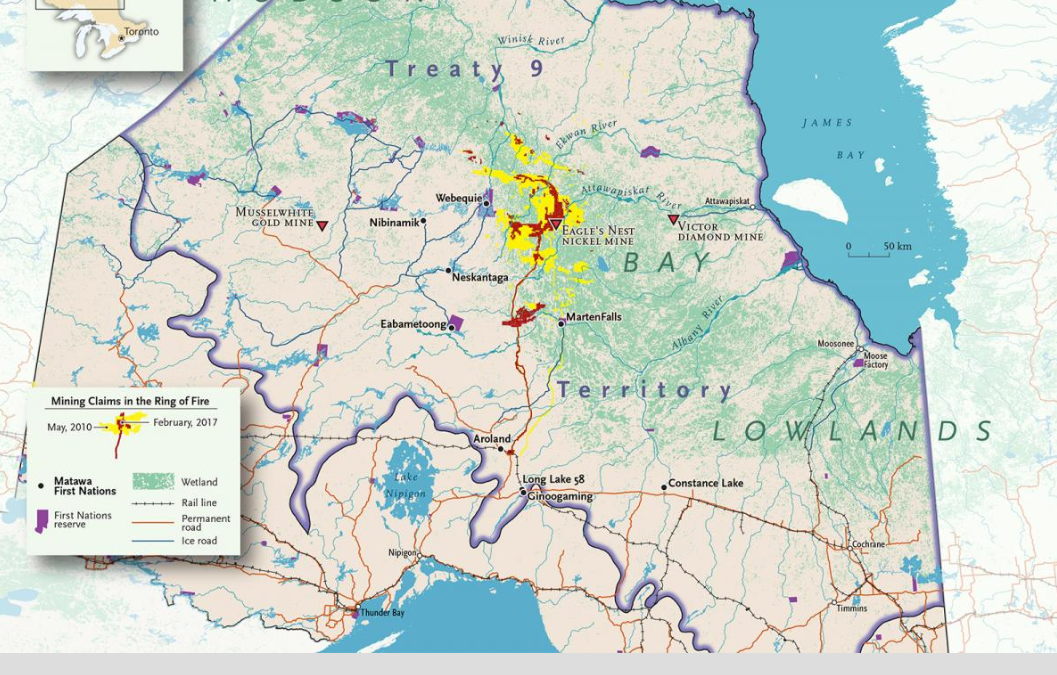

The thunder from down under has been reverberating through Ontario’s Ring of Fire mining camp – located roughly 500 kms northeast of Thunder Bay – as Australian mining giants BHP and Wyloo Metals are fighting a bruising bidding war for Noront Resources. The junior exploration company owns the Eagle’s Nest nickel/copper potential mine as well as extensive world-class chromite deposits and other mineral-rich promising ground.

BHP is the largest mining company in the world, whose current CEO, Mike Henry, is a Canadian, while Wyloo Metals is owned by Fortescue Metals, founded by mining billionaire Andrew ‘Twiggy’ Forrest, and is the world’s fourth largest iron ore miner.

“Noront’s ROF land package hosts some of the most prospective mineral deposits in the world. These deposits have the potential to become Canada’s next great mineral district, supporting the production of future-facing commodities for multiple generations”, claimed a Wyloo Metals news release in August.

The entry of multi-billion-dollar mining corporations signals a proverbial “game-change” in the stalled Ring of Fire mining camp. Noront Resource was a struggling junior company that did manage to consolidate almost half of the valuable mineral claims in the camp but did not have the funds to do significant further exploration or to build their existing mine. Newly established and well-funded explorer Juno Corporation is the largest claim holder who after extensive aerial geo-physics surveys that showcased promising anomalies, is hoping to add to future discoveries.

Many respected geologists feel the Ring of Fire’s nickel, copper, chromite and other battery metals have the potential to equal if not exceed the legendary Sudbury Basin – the source of much of the western world’s nickel for most of the last century. This integrated mining complex is still producing a significant amount of Canada’s nickel and copper production, critical components of zero emission vehicles, which use more of these metals than standard gas-powered engines.

Due to global climate change – reinforced by this year’s unusual droughts, forest fires, floods and other climate anomalies – commitments to decarbonize the transportation sector through electric vehicle adoption and storage technology is gaining political urgency.

During the election, Prime Minister Trudeau pledged to mandate that 50% of personal vehicle sales in Canada be electric vehicles by 2030. Other western governments throughout Europe and the U.S. have similar goals. There are almost 1.5 billion gas-powered vehicles in the world. Without a doubt, this is probably the most significant industrial transformation since the industrial revolution first started in the late 1700s.

However, there is one major problem with Trudeau’s mandate and the global auto sector’s commitment to electrify the world’s gas-powered vehicles. There is not enough nickel, copper and other battery metals to accomplish this worthy goal unless more mines are allowed to go into production. And the mineral that gives Elon Musk and his Tesla corporation real nightmares is nickel.

Roskill, a leader in critical materials supply chain intelligence, forcasts global nickel demand for the battery sector to increase from 92,000 tonnnes in 2020 to 2.6 million tonnes in 2040. Total nickel production in 2020 was roughly 2.6 million tonnes, largely used for stainless steel production.

It’s that black and white! No new nickel mines and the world’s decarbonization initiative to stop global warming will absolutely fail. And environmental groups’ proposals for recycling are just a “Harry Potter fantasy” as this massive conversion is unprecedented in human history.

Canada/Ontario is the second largest land mass in the world. The country’s mining sector is well known throughout the world for its sustainable practices, restoration activities and FNs’ consultations. It is the largest private sector employer of Indigenous people and mining developments routinely provide supply service contracts to Aboriginal businesses.

Almost 30% of the workforce at Kirkland Lake’s Detour Lake Gold mine is Aboriginal, many from the Moose Cree First Nation on whose traditional territories the operations are located. Last year, the company spent roughly U.S.$260 million on firms with Indigenous ownership.

One of the major problems in Baker Lake, Nunavut, where Agnico-Eagle has been mining gold for at least a decade, is that there are not enough parking spaces for all the half-ton trucks, the well paid-Inuit workers have purchased. The company has helped grow an almost non-existent middle-class in the region and the company contributes roughly 25% to the territory’s GDP.

Nothing screams louder than economic reconciliation for Indigenous communities when mining companies provide middle-class jobs, allowing parents to give decent housing and a high quality of life for their children.

Webequie and Marten Falls First Nations are the two communities in the Ring of Fire on whose traditional territories the vast majority of the mineral deposits and the vital north/south 300km road into the camp, are located. Both communities are working on onerous and time-consuming provincial environmental assessments (EAs) in order to get the green light to start road construction.

In a news release, Chief Wabasse of Webequie First Nation; “Our First Nations people have been stewards of these lands since time immemorial and that’s not going to change through this process. One of the main reasons we are leading this Environmental Assessment is to exercise our jurisdiction and inherent rights, … We are hopeful that our neighbouring First Nations will trust us to lead this planning work responsibly, respecting traditional protocols, clan families and environmental concerns.”

Their biggest fear is that the Trudeau government will require federal EAs that will further delay the road construction even though there is a global shortage of the valuable nickel, copper and other battery metals the industry desperately needs to develop as soon as possible.

Marten Falls Chief Achneepineskum says, “Without this project, our people will continue to live in the same underdeveloped conditions, lacking access to drinking water, housing, clothing, jobs, healthcare and education; all the basic needs that other Ontarians take for granted every day, … This project has the potential to finally bring economic reconciliation for remote First Nations in Ontario…”

As with all First Nations communities in Ontario’s isolated far north, water advisories, poor housing, an epidemic of child suicides and high unemployment are issues that the federal government has not been able to resolve for many decades.

Yet, Ontario environmental NGOs and a cadre of left-leaning lawyers are vehemently against sustainable mineral development and have been able to convince three FNs communities – Neskantaga, Attawapiskat, Fort Albany – who have no legitimate claims on the traditional territories in the region, to support them.

They even want to stop the construction of a vital north/south road that will end the isolation of both Webequie and Marten Falls. Many bulk materials are shipped to these isolated communities through a winter road system. Last winter was one of the shortest winter road seasons due to global warming. Most of these winter roads will eventually have to be replaced with gravel all-season roads.

Neskantaga FN is located about 130 kms southwest of the Ring of Fire and is working with a junior exploration company and has other resource development projects on its traditional territories. Since they are upriver from any potential mine development, nothing will affect that community. They are also a very tiny First Nation with an on-reserve population of about 250.

Both Attawapiskat (1,800 people) and Fort Albany (2,000) are roughly 250 kms from the Ring of Fire on the James Bay coast. They are currently working on their own all-season road. Their biggest concern is that any “potential” problems in the mining camp “might” affect their communities down river. We need to put the risk of mineral exploration and mines development into context that southern audiences might better understand. Ontario’s oldest nuclear power plant is at Pickering which is only 45 kms from Toronto’s downtown city hall.

Millions of people in the Greater Toronto Area, the most densely populated region in Canada can live with the low-level risk of a nuclear power plant as there are many rules and regulations to keep it safe. In fact, all of Ontario’s nuclear fleet are located on the Great Lakes which have a population of around 35 million people in their drainage region on both sides of the Canadian/American border. The total Aboriginal population of Ontario’s Far North is about 35,000 people, roughly half of who are living off-reserve.

In addition, the biodiversity (ESG) risk in the Ring of Fire’s boreal forests and swampy muskeg pales by a very, very, significant magnitude to the major nickel laterite producing islands of New Caledonia, Indonesia and the Philippines and their rich tropical rain forests. Nickel laterite deposits are open pit mines while the proposed mines in the Ring of Fire are underground and have a much smaller footprint.

One final key issue is the economic geo-politics of strategic mineral deposits. The COVID pandemic clearly demonstrated the weakness of global supply chains and the need to develop resources closer to North American manufacturing centres. The Ring of Fire’s nickel, copper and other battery metals is a terrific leverage for the province to ensure the next generation of electric vehicle assembly plants are located in Southern Ontario.

If we can’t sustainably mine critical nickel deposits in Canada’s vast northern frontiers that will provide middle-class jobs to impoverished First Nations and play a vital role in the world’s decarbonization initiative to save the planet from global warming, then where do we go?

We are in a climate emergency. The road into the nickel/copper rich Ring of Fire mining camp must become a “green” national and provincial priority!

Ontario’s fanatical ENGOs and left-leaning lawyers remind me of the old fable of the frog and the scorpion. The scorpion convinced the frog to take him across the river, promising not to sting the frog. Halfway across the river, the scorpion does sting the frog and they both drown. The scorpion saying that it was his true nature, regardless of the consequences!

Stan Sudol is a Toronto-based communications consultant, freelance mining columnist and owner/editor of mining news aggregator RepublicOfMining.com

Recent Comments